This Week’s Expert:

James Maddison – the Open Data Institute (ODI)

James has been a consultant at the Open Data Institute (ODI) for nearly four years. As the ODI has adapted and evolved in response to changing global and political environments, James has worked across many relevant topics areas, from open cities and public services, through to data ethics and data guides in response to Covid-19.

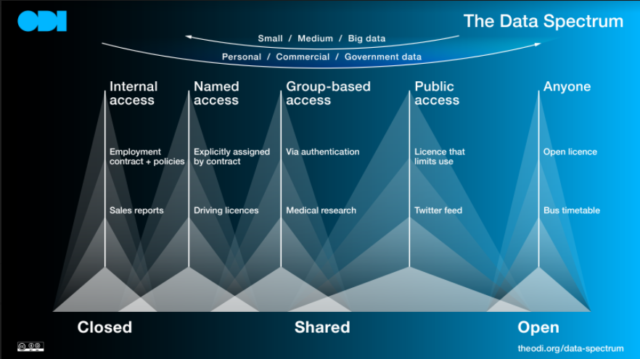

The ODI was set up in 2012. The initial focus was on transparency and accountability: this was a narrative that had traditionally been aligned with the open data agenda, and it is still relevant today in the UK when talking about open data. As time has gone on, the ODI has recognised that not all data should be open, and while it advocates for openness with data, the focus is now about data being on a spectrum: from closed, through to shared, and then to fully open. Now, the ODI works to achieve its goals through training, consultancy, tools, guides and research, and works with companies and governments to build an open, trustworthy data ecosystem.

To start, what is meant by open data?

Our standard definition for open data is ‘data that anyone can access, use and share’. One thing I would add to that: to make data legitimately open, it should also be published under a recognisable open licence. Usually that is an Open Government Licence or a CC BY open licence

Which domains or business sectors have you found to be the most challenging when it comes to adopting open data?

We see it a lot in most sectors as there is generally a resistance to open data from most commercial organisations. There’s usually a desire to use, consume and create things from existing open data, and companies want to have data shared with them, or made accessible to them, but on the flip side they don’t want to make data more available in return. They use the argument that it’s commercially sensitive, or that they might lose their competitive advantage over other organisations in their space. A lot of companies are not ready for truly open data, so a lot of the time, we try to take them through a process of becoming more open with data, by sharing data that they collect more widely.

What we have also found is, if you approach a company by talking about the data first, it pretty much always fails. Unless you’ve got someone sitting in a senior management position who really understands the value of open data, it is very difficult to sell from that angle. You almost always need to go in with a problem that needs solving: a challenge that affects a lot of the big organisations in a sector.

One great example is HiLo – a maritime risk management company funded by Lloyd’s Register Foundation – as it showcases a great journey of a sector becoming more open. HiLo recognised that if more shipping companies shared data with each other, they would be able to identify patterns that occur from small leading indicators. For example you might have a fuel spillage occurring as a result of minor holes or leaks within different parts of the ship. Being able to identify those trends means that the whole shipping sector can find it easier to identify issues before they become disaster events or proper incidents.

However, they found that these companies don’t want to share directly with each other, or for the data to be open data. So what HiLo has done is essentially set itself up as an intermediary. It receives aggregates, creates insights from the data and then shares those insights more broadly across the whole group that are involved in their initiative. The benefit there is that by simply sharing the data you have to collect for regulatory purposes, you can allow that to be compared to data from other shipping companies to gain valuable insights, and you might be able to avoid crashing or losing one of your million-pound vessels that’s transporting a bunch of cargo that you would have to pay the money back for, or deal with huge insurance pay-outs.

“A lot of companies are not ready for truly open data, so a lot of the time, we try to take them through a process of becoming more open with data, by sharing data that they collect more widely.“

How does the open sharing structure of HiLo compare with the data institution concept that the ODI has been doing research on?

Data institutions are organisations who steward data on behalf of others, often towards public, educational or charitable aims. Although the term may be new, there are many important data institutions that play different roles in different sectors and contexts. UK Biobank, for example, was established in 2006 to steward genetic data and samples, and make them available for health research and development.

I would look at HiLo and see them as a data institution. By combining and linking data from different sources, and providing insights and other services back to those that have contributed, it plays a vital role in unlocking value from data that wouldn’t otherwise happen. To me, a data institution is an organisation who is trusted and that has been established specifically to advance a particular purpose or mission.

At the ODI we’ve established a new programme to help to bring about new data institutions and improve the practices of existing ones.

Whilst open data is freely available, will people have to pay for it? There will be a cost to cover in keeping these data institutions running – do you see a commercial model behind this?

This is one of those aspects that is not really established yet but, regarding the sustainability of data institutions and the overall business model, there are several ways that organisations are looking into it.

Often the initiative or the institution is established based on a grant fund or another type of government funding because it has been set up to solve an issue that the government is supportive of. And from there the sustainability of that programme is established as part of the scope of work.

Among the initiatives that we are seeing set up in the private sector, a lot of the models are based on private sector companies contributing to the maintenance of the data institution in the same way that you would co-pay for a project. As a result there would be a shared element of that cost. At the ODI, we are not big advocates of paying for access to data, but rather paying for the kind of skills or upkeep and maintenance of that data.

That tends to be what the funding of data institutions looks like: paying for the skills, maintenance, upkeep, and the involvement from people required in the stewardship of that data.

“By combining and linking data from different sources, and providing insights and other services back to those that have contributed, it plays a vital role in unlocking value from data that wouldn’t otherwise happen.”

What do you think has been the most interesting or promising advance in open data in the last few years in the UK?

There are countries that are doing aspects of open data better than the UK, such as Canada which does open data very well at the government level. It engages with the private sector very well and a lot of that has to start with an open government push and a core open data focus within the national data strategy.

In the UK there are a lot of examples of bigger open data initiatives that the ODI is involved in. One example is OpenActive which is an initiative that looks at creating more visibility of physical activity opportunities in the UK. It does this by convening physical activity providers to provide data about their classes, booking costs and other requirements to attend these such as a gym membership or free access. This kind of information can be very difficult to find on websites of specific companies and this initiative makes all of that data as open as possible by giving access to that data to start-ups, SMEs and other organisations who want to do creative things with it and create apps.

Go Sweat is a good example of one of the startups that are out there creating apps that help you find activities. The service pairs corporate organisations with physical activity providers to give employees discounts and new fitness opportunities.

What excites you the most about the concept of open data?

Probably the open innovation aspect. The idea of making data available for anyone to access, use and share, means that people can create something useful for the world. Citymapper is a prime example of this, as it was able to be created from the mass of open data provided by Transport for London. Not only is it a great tool, but it has spread to other countries as well and showcases how something can be created from the publishing of open datasets.

The idea that people are able to create something from what you might not see as useful, or might not have the time, capacity or skills to do yourself, is the real value of open data.

“The idea of making data available for anyone to access, use and share, means that people can create something useful for the world.“

If you could pick one thing that you would be looking for the British Tech community to achieve over the next 1-2 years, what would you ask for?

The aspect that the tech community would be looking for is more commonality, more definition around data standards and more adoption of existing data standards so that data becomes more usable across different contexts. It’s something we hear all the time across multiple sectors, private and public.

COVID-19 is a great example of where, if there were existing data standards and terminology, we could have created more useful outcomes from data being collected by tools, such as symptom trackers, much more efficiently. A common data infrastructure, being more connected around data in general, and publishing open data in a way that can be useful for as many people as possible, would allow us to communicate much more effectively and allow the same event, such as a pandemic, to be addressed in a collaborative way by the global population.