This Week’s Expert: Dennis Dokter

Dennis is the Relationship Officer at Nexus, the University of Leeds’ innovation hub., Nexus connects businesses to world-class research and expertise across the University, providing bespoke support that delivers real commercial impact and accelerates growth.

Prior this, Dennis worked at Statistics Netherlands (CBS) as Grant Development Manager, acquiring funds for research, particularly for Big Data sources as well as teaching data ethics and the role of research within society. With a strong background in Philosophy and Ethics of Society Science & Technology, Dennis’ specialities are dealing with some of the Big Data questions: What is data, the quality of data and how multiple strands of data sources can lead to a more reliable overview of a situation.

This Week’s Data: Big Data

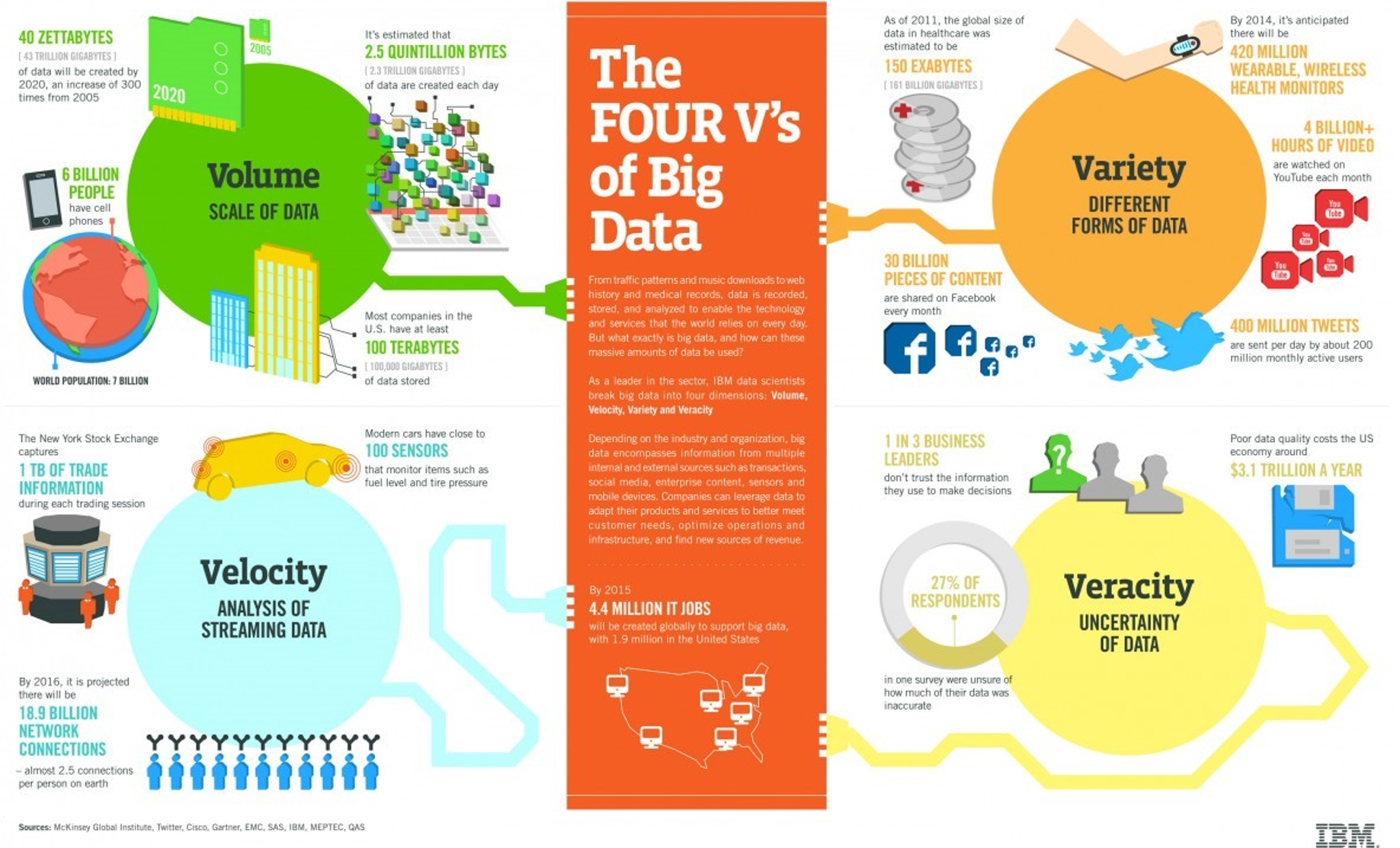

Wikipedia’s Definition: Big data is high-volume, high-velocity and/or high-variety information assets that demand cost-effective, innovative forms of information processing that enable enhanced insight, decision making, and process automation.

Dennis’ Definition: For me, that would be the “4 V’s”: Volume, Variety, Velocity and Veracity:

What excites you the most about Big Data now?

Reality Mining, first coined by MIT, is a concept that really excites me about Big Data. It is a great way of collecting huge datasets from a primary source and giving answers to basic questions quickly by using Big Data sources, which otherwise would be more difficult.

If you look back to when data gathering was more survey-based, it could take 6 to 12 months to get those results back, whereas with Big Data gathered from sensors is much easier and implementable and the refresh rate can almost be instantaneous. This is much more preferable when dealing with micro level data and benchmarking capabilities.

What do you see as the main challenges in getting the quantity and resolution of data needed for Big Data?

One of the main applications of Big Data is when you are trying to answer a specific “What” question. For instance, knowing how many people are walking through a city or how many trains are going in and out of a station. An issue that often is not taken into account is the missing data, for example scanner data from supermarkets – it all depends of whether the individual supermarket has shared, or are willing to share, their data, or whether particular users are under/misrepresented. Are you getting everything you want to get? And this still doesn’t address the big question of why the data is relevant to the questions you are trying to answer.

We often ask what data is available, but do you think that is the wrong question?

Very often it needs to be approached from the problem you are trying to solve. If you start by asking a question, for example the reason for closing a street in the city, you then need to know how the street is being used and by whom. Big Data can give you those answers around what’s happening in that street. Another example is cars or cyclists: How many cars are passing through it, how they are passing through it, and how often are they standing still? But Big Data cannot help you go deeper into why the cars passed through there in the first place. If you want to figure out how to make public transport more attractive, just simply looking at the data won’t give you the answer You need more data around the cost, traffic diversion and other data that will convince people whether or not to use public transport.

Is it a different type of data that needs to be collected?

It’s about clearly setting the parameters, so yes I think it should be about collecting more qualitative data.

You can see this more in methodologies such as human centric design, or the social construction of technology where technology is shaped by human action and their motivations, it is all about co-creation. Very often these motivations will give you certain trigger words that help you identify Big Data sources you can use to collect data that’s more focused and quantitative based for accurate measurements.

Could you expand on what you mean by the “fairness” of data?

I mean the democratisation of data. Many large corporations are gathering a huge amount of information, but of course it is the public that are often creating this data. What we need is a fairer system of data collection where you become in charge of your own data – a self-service type of technology where data is kept with the individuals, and corporations would have to request access to it, the individual could therefore always determine whether they want to share it or not.

However, I don’t believe that everybody will be able to share data openly. There are a lot of good initiatives where open data platforms allow people to unload data freely, but you’ll still see large datasets that will never be put onto those platforms because they contain private information. By using a more individual-centred self-service approach to data, we might be able to perform analytics on provided data without sharing the whole private dataset.

How do you see individuals being consumers of this type of micro-level controlled data?

Getting there requires a form of data awareness but, in order to create a more flexible world and for citizens to be able to transfer data or to move around themselves, having like a personal cloud-based solution where you can store all your data will be very useful.

One of the situations where this type of personal cloud-based solution would be most useful is when sharing your data with hospitals, or hospitals sharing your data. One of the things that I notice coming from the Netherlands is, as my medical data is still in the Netherlands, I can’t transfer it here digitally or give it to the hospital. I don’t think that’s necessary at the moment, but it would be handy if there was a better system in place. For instance, my health data would be on a personal cloud and then, when I get admitted to hospital, I’d be able to give access to my data to that hospital for the specific time of me being there, creating better care than if there’s a lot of bureaucracy in getting or transferring the data from hospital to hospital.

So it would liken to a form of blockchain or distributed ledger that was acting as a secure “Data Wallet” that moves between organisations you decide to share it with?

Exactly. It would be like a personal vault and, through a distributed Ledger with blockchain, you’d be able to track every movement of your data and every interaction with your data, which would create that personal security of being able to see when you have given that access and to see when the permission of that access has stopped after the specified period.

If you’re in hospital or the GP surgery there is a clear benefit to sharing your data. But what about healthy individuals? How do you motivate people to share data when there is not an immediate need?

The motivation comes from having the choice as to whether you share data or not. You can put the data you want in that “vault” based on preference and what interests you. An additional motivation is that storing your data in this vault would be more secure than storing it on your phone or your personal computer, which is not necessarily the safest place to have it stored.

The bigger question is how can we increase people’s data awareness? We create a lot of data in our day-to-day lives without realising it. We often share it with Google and Apple for instance. But there are also sharing models where somebody asks permission to use your data for research and they only get access to specifically what they need. They might even pay you a small fee. It’s this kind of model that shows that there’s a benefit in it for me, it’s safe, and I can contribute in my own way and on my own terms in how I transfer and share my data.

What type of organisation should control these data vaults? Private or Public?

When you raise that question with people, the issue that always arises is the question of ownership – who owns the data? Are we owners of the data we created and, if that’s the case, do we have the right to say what happens to our data? This is the first hurdle to take.

From there, it creates the opportunity to talk about it and start creating organisations that act under a union-type structure where we can act as part of this union on how to deal with certain types of data. We discussed this at MIT, for instance, Uber as a corporation has data, but it would be the Uber drivers who would be saying whether they are willing to share their data. But therein lies the problem: The main business model for these corporations is the data.

We have to find a way of breaking through that paradigm of data ownership, and communicate to people that if they actually want to be able to use Big data on a micro level and in a faster way whilst avoiding data issues, you need to be talking with the people themselves in order to get the data.

Moving away from individuals, how do you see smaller companies being motivated to share data about their staff and their business?

One of the primary benefits companies have, especially if they are local, is that their data is local to an area: it represents the uniqueness of that area or region, and by sharing that data they can benefit from combining it with other local companies’ data.

This doesn’t necessarily mean that data is open, or that it has to be open. There are multiple ways of sharing data and performing analytics on the data without making it open. Take Multi-Party computation for instance, where you again work with a distributed ledger. You create a smart contract and encrypt all the data, send it to a trusted third party where it is collected, collated, and partitioned in a way that you can work with it, but that third party has no idea what’s in the data. It only knows how to run the queries, sends the results back, and that’s how you’re able to share the data in a way that you actually not sharing it, but you still able to get like the benefits of combining the data.

For instance, if you often have insurance companies, health care companies, and technology companies working in similar fields and therefore they don’t feel comfortable in sharing that data because that’s their business model. Their results are the reason why the NHS would choose them as a distributor. That doesn’t mean that combining that data with other companies doesn’t have a huge added value, and this method would create those opportunities.

Is this similar in concept to the Open Data Institute’s research which explores the possibility of sharing data but still having a level of control over who gets access to it, what for and the purposes for sharing it?

Similar, yes, in the sense that the principles are equal. However, the ownership of such a platform will always be the biggest point of discussion: Who will be this trusted third party? And should this be a governmental organisation or governmental body, or should it be a private organisation? Or does it have to be a mixture in between? I think what you need is a lot of computing capabilities. Combining these datasets, being able to do this kind of safe research, requires a lot of investment, so it’s about figuring out how can we create this and then starting a pilot somewhere. I think that a party like Nexus and the University of Leeds or ODI Leeds can play a huge part in that.

You mentioned that we need a lot of computing capabilities to drive this concept of controlled Data Vaults: But for every part of that process, a cost is building up. Who pays for it?

It depends on who is benefiting from it.

If you look at how data can be used on an urban level, you’ll need a data ecosystem with local parties who are generating data that you can use in order the solve certain urban issues, such as street pollution, public transport, improving the school system etc. Because the benefits are mainly in line with the city and its citizens, that cost becomes a public responsibility.

But how can you get your return on that? It would be as a result of that data ecosystem: As a result, you can be a more efficient local body, thus attracting higher skilled employees that are able to mitigate with all these different parties that have an understanding of what’s happening with the data. You will then have less staff working on creating services, or doing their own research, because you will be able to do it with the local parties. In that sense, you are also creating a better partnership with your local companies, creating a better interdependency of how everything works, and creating a better overview that allows for saving on money.

If you want to be a SMART city, you want to be able to know what’s going on. And for that you must have a SMART way of monitoring. You can’t get that from a single data source, you must work with all the different parties involved to fit those pieces of the puzzle.

Is the business model similar to cloud computing or more like a car sales process?

I think it’s more in the range of the cloud computing for reasons such as collective agent-based modelling. So what you can do through qualitative research is identify these collective groups and then you can identify the sample size that you actually need to get an accurate result, which means you wouldn’t have to constantly monitor everything that’s going on. It all depends on the timeliness, but you create a dashboard with different numbers instead of getting to one general outcome.

I think that the main issue will be getting people to understand the correlation between all the numbers and finding the answer.

Do you have a use case that describes what ideal situation and environment for this would look like?

It’s very similar to what we’re trying to do at Nexus. You’re trying to set up an ecosystem between academics and SMEs that are already working together. You want to connect these companies with each other. We have the MIT REAP program where we also work with other parties within Leeds. It means you already have a structure that you can use in order to create a better ecosystem within Leeds using these organisations that are already familiar with each other and are willing to work and research together. You can then use this setup to identify the main issues and research questions and then use that network to supply the answer.

How do you see issues such as bias, generalisation, and cherry-picking on facts being dealt with?

What I hope is for an open platform where people and companies can come and be a part of it and be able to scrutinise the numbers. I also hope that this will encourage people to share the methodology they use. Whilst the data is important, it is also interesting to know the methodology used on it: How are you combining the data?

On the other hand, the way policies are formed are rarely themselves open or transparent. Bias is very often intricate and in most datasets; and in order to reduce it we need to try and involve everybody by getting them to create and be a part of the ecosystem. Very often, decisions are being made from just one or two research papers, despite there often being 9 other papers saying the exact opposite elsewhere. By creating a Smart Dashboard that is open for scrutiny, you can make changes in an unpolitical method as possible. Politics come into play after the data has been visualised.

Transparency often introduces extra liability to both public and private organisations which is a reason not to adopt this kind of platform. Is there a way to show that, whilst transparency has its challenges, it’s overall better for you?

It’s a difficult process of breaking open Pandora’s box and asking why policies are made the way they are, and why did we star using them in the first place if they are not working? It’s a form of awareness that needs to start with public bodies as it’s a form of public responsibility. We have sustainable development goals that we set out with the United Nations; We have our European Societal challenges; even the UK has their own platform with the main challenges they want to address. But we have to be open about what we’re addressing otherwise we are not working in a data democracy.

We’re working in a data dictatorship where we just get to see what they want us to see. It may be a slight generalisation, but if organisations are so confident about the numbers that they are publishing, why are they not open about the methodology?

If you could get the Nexus and Leeds community to come together to do something crazy over the next 6-12 months, what would you want us to tackle?

This is something that Statistics Netherlands is already doing, but I would suggest that Nexus, along with the University and the wider Leeds City, to start an Urban Data Centre where you create the opportunity for data to be combined, or where research can be done together, in order to look at regional problems. The general goal would be to serve the city of Leeds and its citizens by putting our shoulders together and see how we can tackle challenges as a community.

What do you think are the key things to bear in mind when we talk about fairness of data?

The main thing that we should focus on is the pitfalls that are out there. There’s a lot of them and I’m still working on the list. I think in research we have to be admitting that it is never complete and it’s never finished. We should always be open to being able to plug in new data to admit that maybe there is no correlation and to confess when data sources aren’t as useful as we thought they were.

We also need to learn to not rush into generalisations. There will always be something you have to revalidate as time goes on.

We also need to be bearing in mind how we communicate and publish our research. How does it get picked up by news channels and consumed by the general public? There’s a lot to take into account when we work with data, but I do believe that being transparent, and admitting to this, would be one of the biggest steps in our society.

Overall, the biggest problem in general is not sharing our data or simply cherry-picking data sources. By laying down our responsibilities, why you did what you did and how you could do things different is going to be very important on the road to being more transparent.

We hear you are currently writing a book on the subject of Big Data?

In my private time I am trying to collect all my different thoughts and ideas and put them into a framework to see how this can actually be worked out. I have been privileged to talk to a lot of interesting people, professors and researchers throughout my work, and I want to see if I can collect all these ideas and eventually bring it out of the theoretical and into practice in order to justify and respect their visions as they have inspired mine.